Nursing shortages have been predicted worldwide, with headlines reporting that this is one of the dominant issues in healthcare today. Nursing attrition is on the cusp of becoming a crisis, with perilous implications for patients and healthcare providers alike. Can anything be done to mitigate this nursing crisis?

The Victorian era was known for its hierarchal social order, where upper-class males enjoyed a privileged lifestyle with great wealth and education. The expectation that women would marry and take care of the household and children meant access to higher education and the pursuit of careers were restricted.

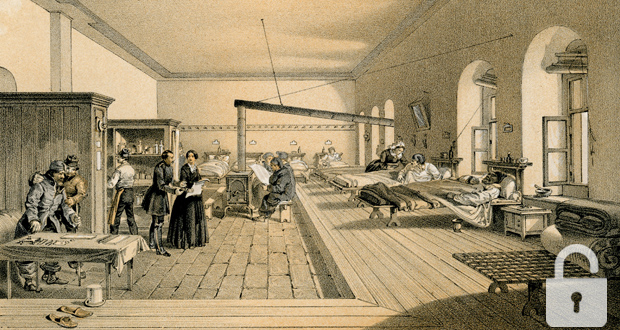

The medical profession in the late 19th and early 20th century is often characterised by male physicians and surgeons giving unambiguous orders to female nurses. The nurses dressed in demure color-coded, floor-length uniforms identifying their level of rank. This depiction may reveal some insight into the sexual discrimination that was prevalent at this time.

In 1820, Florence Nightingale was born to an upper-class English family. In 1851, despite the intense objections of her family, she was keen to join the noble profession of nursing: so keen in fact that she enrolled as a nursing student in Germany (there was no training for nurses in the UK at that time). Her nursing career started during the Crimean War (1853–56) where she is recognised for nursing the injured and dying soldiers as well as raising hygiene standards.

In 1859 she wrote a book, Notes on Nursing, which is still considered a classic. Her achievements were truly remarkable given that, in 1860, she opened the Nightingale Nursing School, whose mission was to train nurses to care for the injured and sick. Her greatest work is said to be professionalising nursing roles for women,13,14 but arguably her lasting impact may be as a trailblazer and a feminist.

Nightingale is credited as the founder of nursing, which in Australia is currently the largest single health profession. Nursing in the 21st century requires the provision of high-quality care to discerning patients while dealing with increasingly complex caseloads. In 2012, there were 273,404 registered nurses (RNs) and almost 60,000 enrolled nurses (ENs) registered in Australia, many with postgraduate or doctoral degrees.15

Patient and family-centred care, empathy and compassion are core fundamentals for all healthcare professionals. Empathy is the capacity to understand what another is feeling. Whereas, paradoxically, compassion is the capacity to co-suffer with another; it is the desire to alleviate another’s pain or suffering. Emotionally intelligent nurses have both interpersonal social competence as well as intrapersonal self-awareness, which allows them to engage well with each other and with their patients.7

Most nurses adapt positively to stressful working conditions, manage their emotional demands, foster effective coping strategies and improve wellbeing and enhance professional growth,4,5 which in turn promotes optimism, humour and hope.3 Personal resilience is required if one is to survive and thrive in the healthcare sector. Fortunately, resilience does not have to be innate, it can be taught and developed if one is willing to engage in self-development that promotes psychological flexibility and positivity.6

After hearing harrowing stories told by patients, with intensity, sincerity or frequency, a nurse may be affected in a vicarious way – experiencing the emotional journey through empathetic imagination. This can have a heavy impact on one’s personal resources, including compassion, a well-recognised phenomenon known as ‘compassion fatigue’.1,2 To counter this would be to flourish.

Flourishing is a central concept in positive psychology that includes positive perceptions, attitudes and expectations. It incorporates two dimensions: feeling good and functioning well. Nurses who feel appreciated and acknowledged, and where possible have a sense of autonomy in their workplace, are invariably energetic, dedicated, self-determined, focused and positive, and they will find meaning and purpose at work.

Developing a positive mindset and flourishing was popularised by Irish philosopher Gertrude Anscombe, and this concept has been extended by Corey Keyes and Barbara Fredrickson. They hypothesised that optimal wellbeing and flourishing increased with age, education and confidence,18 therefore accommodating this in workforce planning may promote nursing tenure and endurance.

It has never been more important with workforce planning to nurture new graduates as they gain experience, skills and proficiency in healthcare. Failure to do this may contribute to the worldwide shortage in registered nurses. Millennials tend to have more than one career over their lifetime given their heightened expectations of appropriate remuneration, conditions and career opportunities. Unfortunately, there are global estimates that by 2020 there will be a deficit in registered nurses by approximately 20 per cent.24 In addition to recruiting new staff, it is important to retain senior staff, creating a multigenerational skill mix that has benefits, such as a broad range of skills, mentoring for new staff, better reasoning ability with greater clinical oversight as well as a greater depth of work experience. Aging in this context is viewed as a positive attribute. Senior staff members tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction, are more committed to their organisations, are less likely to transfer to other healthcare facilities, and have fewer sick days and workplace accidents. Seasoned staff are also more likely to know how to wield the organisation’s culture and deal effectively with administrators and others to ensure the safety and wellbeing of patients and families.11

Professional development progression can be enhanced by using an array of online personality tests that highlight a person’s strengths. Flourishing nurses have a natural inclination towards positive energy, and these tests reveal emotional intelligence traits, and linguistic, logical, spatial and social skills.

Introspective evaluations may provide the impetus for developing a positive mindset, particularly when supported by the team leader. Two such evaluation tools are Diener’s eight-item Flourishing Scale (FS), which measures self-perceived achievement, self-esteem and optimism;21 and the Losada Ratio which is used primarily to distinguish flourishing from floundering people. Harnessing employees’ natural positive traits and nourishing their strengths will inspire both accomplishment and productivity. In addition, professional performance, staff retention and flourishing teams can be enhanced with peer empowerment, encouragement and engagement. When these three factors are embedded in nursing, there is an increase in quality patient care, satisfied patients, greater productivity, motivation and a positive healthy work environment.19

According to the 2017 survey Australia’s Healthiest Workplace, 50 per cent of Australians have at least one aspect of work-related stress. In the same year, a UK survey on wellbeing in the workplace, published by Damian Stancombe, noted that 66 per cent of workers admitted to coasting, and 7 per cent of employees admitted to struggling or floundering. Being mindful of these ratios, organisations may need to change their culture, recognise and turn unfavourable situations into great opportunities, and be the vanguard of progressive healthcare.

An innovative Swedish study, known as the Svartedalens experiment, promotes flexibility and a better work-life balance. This two-year study looked at the effects on nurses working a 35-hour week (paid for a 40-hour week). Though an expensive experiment, there was no sick leave reported over the two-year period, 20 per cent of staff reported being happier, and there was a 64 per cent increase in efficiency and productivity.26

Countries such as Japan and South Korea focus on the importance of job security, with most employees either on permanent or ‘lifetime’ contracts. Long-term strategic planning is possible due to workforce predictability, in addition to enhanced productivity given the seamless, consistent workflow.

The OECD Better Life Index compares 35 similar countries in regard to work-life balance, social connections and work-life balance/health status. In the 2018 index, the Netherlands outperformed all other OECD countries, including Australia. Less than 0.5 per cent of Dutch people work more than 50 hours per week. This is similar to Denmark, where 75 per cent of Danes have a paid job, but only about 2 per cent of employees work very long hours. Denmark was ranked first in the 2013 World Happiness Report and first again in 2016.30

It is therefore vital to be innovative and flexible, provide job security and positive leadership, enhance education, and celebrate and validate members of the team who meet or exceed those expectations. We know from Viktor Frankl that meaningful purposeful engagement in the workplace has both immediate and long-term benefits, such as cognitive and physical longevity. Job satisfaction has a strong correlation with life satisfaction. It is known that dissatisfied employees are more prone to depression, including ill health and ischaemic heart disease.19 Depression has been linked with limited cognition and low engagement, burnout, resentment and apathy. Conversely, positive psychology and optimism aim to redress this imbalance with improved levels of happiness and wellbeing as well as greater job satisfaction. Psychological wellbeing is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease.20

Aristotle believed that happiness depends on ourselves, and should be the central purpose of our lives both personally and professionally.17 Spector suggests that flourishing teams are happier, more co-operative, more helpful with their co-workers and more loyal to their organisation, and they tend to use time more efficiently as they pursue intrinsically satisfying goals with vitality and passion.19

A unified, robust workforce plan for the acute hospital sector (both public and private) with flexible working hours will positively impact on attrition rates and health service delivery. According to Rodolphe Dutel (founder of remotive.io), employees need flexibility to do their best work and enjoy life. High-quality nursing requires good governance, robust quality management systems, including a recognition and reward system for top performers and team milestones. Enforced human resources policies will promote respect and safety in the workplace.

Regular professional development progress reports will provide an opportunity for maximising timelines and acknowledging accomplishments.9 If nurses are motivated by a belief, with evidence, that they are making a difference in the patient’s journey, this will keep them invested and enriched in the whole experience of healthcare. Research tells us that grit, determination and perseverance are in direct proportion to workplace satisfaction and happiness.9

Organisations that invest time in their staff will reap the benefits of individuals and teams working at maximum performance, despite the tensions and challenges of staff-to-patient ratios and busy caseloads. Teaching nurses to flourish is a powerful and worthwhile investment and this in turn will have a tangible impact on the organisation.21

Organisations that invest time in their staff will reap the benefits of individuals and teams working at maximum performance, despite the tensions and challenges of staff-to-patient ratios and busy caseloads. Teaching nurses to flourish is a powerful and worthwhile investment and this in turn will have a tangible impact on the organisation.21

In fact, it could be said that the achievements of Florence Nightingale in pursuing her nursing career in the 19th century has inspired females in the digital age to aspire to greatness, whether choosing careers within or outside the healthcare profession.8,10

Tona Gillen is nurse manager, trauma, at Queensland Children’s Hospital.

References

1. Figley CR. Brunner-Routledge; Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: 1995. pp. 1–20.

2. Françoise Mathieu. Compassion Running on Empty: Compassion Fatigue in Health Professionals Compassion Fatigue Specialist (Published in Rehab & Community Care Medicine, spring 2007).

3. Harvey Max Chochinov. Dignity and the essence of medicine: The A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ. 2007 Jul 28; 335 (7612): 184–187.

4. Morrison, T. (2007) Emotional intelligence, emotion and social work: context, characteristics complications and contribution. British Journal of Social Work. 37, 245–63.

5. McDonald, G., Jackson, D., Wilkes, J. and Vickers, M. (2012) A work-based educational intervention to support the development of personal resilience in nurses and midwives. Nurse Education Today. 32, 378–84.

6. Chen, J-Y. (2010) Problem-based learning: developing resilience in nursing students. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 27, 230–3.

7. Bonanno, G. A. (2004) Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 59 (1), 20–8.

8. Buerhaus, P. I., Staiger, D. O., & Auerbach, D. I. (2000). Implications of an aging registered

nurse workforce. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 2948-2954.

9. Potratz, Elizabeth, "Transforming Care at the Bedside: A Model to Promote Staff Nurse Empowerment and Engagement" (2012).

Master of Arts in Nursing Theses. Paper 39.

10. Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN et al. Implications of an Aging Registered Nurse Workforce 2948 JAMA, June 14, 2000—Vol 283, No. 22

11. Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, FAAN, FAANP(h); Lucy E. Skinner, BA; David I. Auerbach, PhD; and Douglas O. Staiger, Four Challenges Facing the Nursing Workforce in the United States PhD Journal of Nursing Regulation Volume 8/Issue 2 July 2017

12. The Social Cure. Identity, Health and well-being – Jolanda Jetten, Catherine Haslam and S Alexander Haslam. Psychology Press. 2012.

13. Florence Nightingale and Gerard Vallee (Editor) (2003). "passim, see esp Introduction". Florence Nightingale on Mysticism and Eastern Religions. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-413-6.

14. Bostridge, Mark. Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008.

15. https://healthtimes.com.au/hub/nursing-careers/ Seabreeze Communications Pty Ltd, ABN: 29 071 328 053 in Australia

16. Health Workforce Australia 2014: Australia’s Future Health Workforce – Nurses Detailed. Department of Education /uCube Higher Education Statistics.

17. Aristotle. (2000). The Nicomachean ethics (R. Crisp, Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

18. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. CLM Keyes, D Shmotkin, CD Ryff Journal of personality and social psychology 82 (6), 1007

19. Spector, P. (1997). Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes and Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage Publications.

20. Boehm, J. et al. (2011). A prospective study of positive psychological well-being and coronary heart disease. Health Psychology, 30, 259-267

21. Positive Affect and the Complex Dynamics of Human Flourishing. By Fredrickson, Barbara L.,Losada, Marcial F.

American Psychologist, Vol 60(7), Oct 2005, 678-686

22. Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247-266.

23. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/nursingprojections.pdf

24. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/

25. https://www.businesspsychology.com/

26. http://tony-silva.com/eslefl/miscstudent/downloadpagearticles/6hourdaysweden-nyt.pdf

27. White Paper: The talent shortage continues - How the ever-changing role of HR can bridge the gap http://bit.ly/1xVonjD

28. www.barnett-waddingham.co.uk

29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-dnk-2016-en

30. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/denmark/

31. Reivich, K & Shatté, A. (2003). The Resilience Factor: Seven keys to finding your inner strength and overcoming life's hurdles. NY: Broadway Books.

32. Styles, C (2011) Brilliant Positive Psychology: What Makes Us Happy, Optimistic And Motivated

33. Masten, A.S. (2001). Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227-238.

34. Masten, A.S, & Wright, M.O. (2010). Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery and transformation. Handbook of Adult Resilience, 213-237.

35. Tedeschi, R.G. & Calhoun, L.G.(2004). Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence, Psychological Inquiry,15,1-18.

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Nursing Review The latest in heathcare news for nurses

Nursing Review The latest in heathcare news for nurses